GO Malta

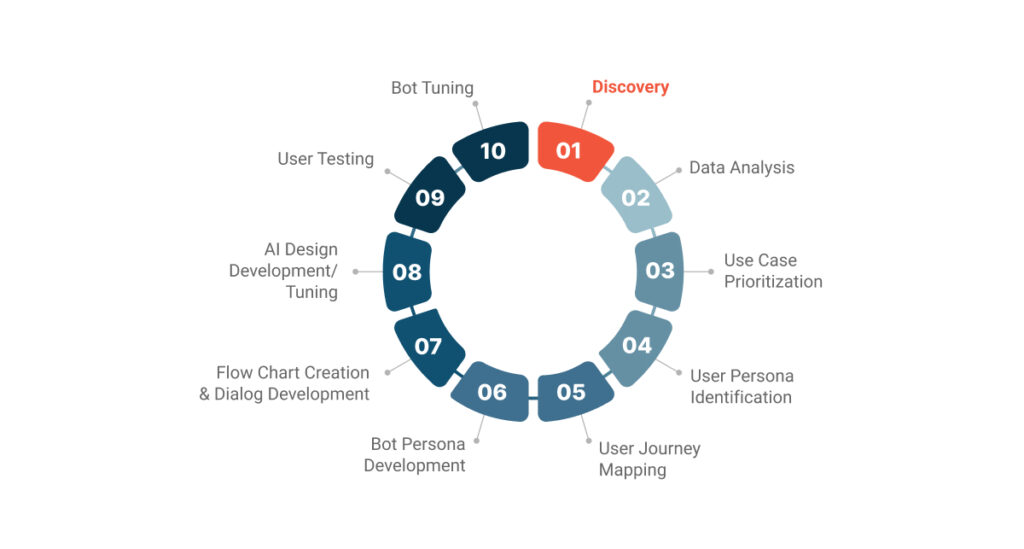

Audit

-

Documented bot persona & tone of voice

Documented bot persona & tone of voice

-

Outlined main flows based on the analytical data

Outlined main flows based on the analytical data

-

Conversation design workshops from experts

Conversation design workshops from experts

Master of Code Global delivered a comprehensive chatbot audit with a future-ready framework for Generative AI integration

Learn More

Dr. Oetker

Chatbot

-

Engaging virtual assistant

Engaging virtual assistant

-

Authorized contest entry

Authorized contest entry

-

AR filters on Instagram for more fun

AR filters on Instagram for more fun

Giuseppe Virtual Assistant on Messenger promoting the Easy Pizzi product and driving engagement for their contest.

Learn More

Burberry

Chatbot

-

Enhanced buyer engagement and loyalty

Enhanced buyer engagement and loyalty

-

Increased online sales and revenue generation

Increased online sales and revenue generation

-

Strengthened brand image and differentiation

Strengthened brand image and differentiation

Master of Code Global developed a Conversational AI concierge, integrated into Facebook Messenger, for a luxury global brand.

Learn More

GenAI Bot for Insurance

-

Streamlined claims processing

Streamlined claims processing

-

Reduced risk of non-compliance

Reduced risk of non-compliance

-

Improved policyholder engagement

Improved policyholder engagement

Master of Code Global developed a Gen AI-powered virtual assistant to provide instant, compliant answers to diverse insurance queries

Learn More

GenAI Virtual Assistant

-

~25%

increase in webchats

~25%

increase in webchats

-

500,000+

web dialogs in 2023

500,000+

web dialogs in 2023

-

1.5M+

interactions with the bot

1.5M+

interactions with the bot

For a global professional hub, we developed a conversational solution with AI-driven routing for member interactions that resonate

Learn More

Aveda

Chatbot

-

+378%

growth in lifetime users

+378%

growth in lifetime users

-

6,918

bookings in 7 weeks

6,918

bookings in 7 weeks

-

7.67x

weekly booking increase

7.67x

weekly booking increase

Master of Code created the appointment booking Aveda Chatbot, with an additional feature set to connect users to their customer service team

Learn More